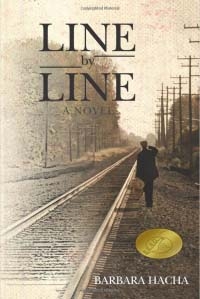

During the Great Depression, Maddy Skobel, my main character in Line by Line, reacts to her first real Thanksgiving dinner. Maddy is a hobo who has been welcomed into the home of Phillipe and Francine Durrand:

During the Great Depression, Maddy Skobel, my main character in Line by Line, reacts to her first real Thanksgiving dinner. Maddy is a hobo who has been welcomed into the home of Phillipe and Francine Durrand:

That afternoon, as I watched Phillipe carve a whole turkey, I thought about families. In New Harmony, my family’s Thanksgiving Day never looked like the illustrations in Harper’s Weekly or the Saturday Evening Post. . . I had never been part of a dinner where just one big, plump, stuffed and roasted golden brown turkey with drumsticks was brought to the table whole and served at one time.

I thought about how there were two kinds of families: the ones made up of people related by blood, which you’re automatically part of, like it or not, and the families you choose for yourself. Today Francine and Phillipe chose to include me. I knew I was lucky, because there was a very large hobo family out there that didn’t have enough to eat.

Because Maddy was a hobo, I needed to research how hobos lived—and survived—the Great Depression. That quest took me to Britt, Iowa, where the National Hobo Convention has convened each August for 116 years. There I met and talked with hobos of all ages, and I discovered the meaning of the hobo family.

The surprising thing was that the hobos come from all walks of life. Some are well educated, some are not. Some have had careers in business, law, and higher education, and others have survived by doing odd jobs and manual labor. Some hop trains—catch out, in hobo terms— for adventure; others do it strictly for transportation. It doesn’t matter. They look out for each other, they share food and other resources, and they honor their dead as a family.

One hobo, named Tuck, talked about safety:

“A big thing for hobos is being safe. We gotta deal with the freight yard, the train itself; we gotta deal with the bulls, and other people who don’t like hobos and think we’re a bunch of bums. They don’t understand we’re a working breed of people.

“There’s just so many things you gotta know just to stay alive and get to where you’re going. Little things, like don’t put your fingers in the track of the door, don’t be catching trains on-the-fly, don’t hang your feet out the boxcar when you’re riding because you could hit a switch or another train could be coming by, don’t lean on the doors when you’re riding because those doors fall off. When you’re going down the road and if you’re leaning against one of those doors and it falls off, well—you’re done.”

Another hobo, Long Lost Lee, described his experiences finding and sharing food during the Depression:

“There were half a dozen of us young hobos. We were under a bridge and decided we would all go out and bum our food and bring back what we could and then we would divide it up.” Sometimes, when they’d knock at a door around dinnertime, Lee said, the people would tell them, ‘Sure, come on in and clean up the table,” offering whatever was left from their dinner. The hobos would take it back to the jungle—their hobo camp—and everyone would share the food.

The hobos share other resources, too. Recently, a hobo had arrived at Britt for the convention and experienced a painful dental problem. Several hobos took him to the town dentist. While he was receiving treatment, the hobos went back to the jungle and took up a collection. Everyone gave what they could, and by the time the dental procedure was complete, the hobos had enough money to pay for it.

Every year, early in the convention, members of the hobo family who have died—caught the westbound—are honored and remembered. A section of the cemetery in Britt is reserved for the hobos. In front of a large cross built from railroad ties are two neat rows of grave markers. A few are granite and have been professionally carved, but most are made of thick concrete and have been hand carved by a fellow hobo. The markers are simple, giving the hobo’s moniker, years of existence, and sometimes are embedded with an object meaningful to the hobo, such as a treasured belt buckle.

The hobos honor their dead by performing a grave-tapping ceremony that is a type of roll call. The names of the deceased are read and the hobos, carrying their walking sticks, form a procession and tap the graves as they walk slowly by. “As long as we remember them, they’re not dead,” the announcer said.

Like any family, the hobos have conflicts and disagreements—and, sometimes, bad behavior. There is, after all, no perfect family. But it was evident to me that they respect each other, care about each other, and help each other when they can.

I think about that after this brutal, mean-spirited—even hate-filled—election. It seems that we have strayed so far from being a family of humans. What happened to that respect for others, the caring for others, and sharing what we can? I think we all can learn a lot from the hobos. It’s time to start paying attention.

Barbara Hacha

I love this ,It made me shed a tear… my gr gramp Thomas Dennison was said to have jumped a train from Utica NY back 1925/26 never heard from again,often wondered if he became a Hobo because we can not find a death record for him and have searched for 30 yrs but I smile now that I read this ,..thank you and I think I can now say ..Rest in Peace Gr Grampa Thomas Dennison…