Every schoolchild knows the bare bones of the Pilgrims’ first Thanksgiving story. Inexperienced settlers who came to the New World for religious freedom would have starved during their first year in Plymouth, if not succored by Indians who taught them how to raise corn adapted to New England’s climate. The Pilgrims feasted to celebrate their successful harvest, and invited their Indian saviors.

That, in a very small nutshell, is what happened. Here’s the rest of the story:

The 1620 settlers were a mixed bag. Many were Calvinist Separatists who took refuge in Holland in 1608 to escape persecution by the Catholic-leaning King James. A decade later, the Dutch were growing weary of cultural differences with the Saints, as the English Separatists called themselves. The feeling was mutual. The Dutch loved celebrating the Sabbath with a pot of beer, the Saints’ children were speaking Dutch, and falling into ‘extravagante & dangerous courses, getting ye raines of[f] their neks, & departing from their parents.’

In 1617 the Saints decided that if they were to remain pure, they had to leave Holland. They sent agents to London to search out a place to settle in the New World. The original choice was Virginia, but Thomas Weston, a London ironmonger, persuaded the Saints to let him and his friends finance the expedition and send it to New England. In return, the settlers would repay their financiers with New England’s cod and furs.

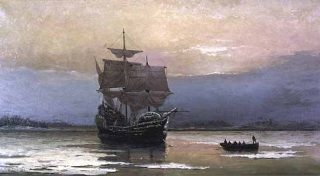

Forty-six Saints left their Leyden homes in July, 1620 and traveled to Southampton, England on the Speedwell. There they anchored beside the Mayflower, which was loaded with farmers and shopkeepers, a professional soldier, and a few craftsmen and mariners recruited by Weston’s ‘merchant adventurers.’

The two groups did not know each other when they set sail for America on August 5th. They didn’t get far before Speedwell developed serious leaks and both ships returned to England. Mayflower was hastily reloaded with 102 passengers, and departed again on Sept. 6th. Between the late departure and a stormy voyage, they did not arrive at Cape Cod until Nov. 10th. There, to settle various discontents, the men signed the Mayflower Compact, combining themselves into a ‘civill body politick’ and promising ‘all due submission and obedience.’

The Pilgrims had a hard struggle that first winter. They lived on the dark, crowded Mayflower while building crude shelters and a fort at Plymouth. The settlers robbed corn and beans cached by the Indians to fend off starvation, but scurvy and other diseases were rampant. Half of the company died.

Relations with the Wampanoag Indians looked ominous. The Pilgrims met resistance soon after arrival with an exchange of arrows and bullets described as ‘huggery,’ but after that the Wampanoags avoided them. The Pilgrims, severely weakened by their horrendous winter, were puzzled that the Indians hadn’t fallen on them.

Though they had found some Indian burials, the Pilgrims did not know that the Wampanoags were also seriously weakened by disease. A smallpox-like plague had all but emptied the Massachusetts coast of Indians, leaving vacant village sites and fields for the Pilgrims to occupy.

They also didn’t know that the surviving Wampanoags were very worried by their powerful neighbors. The Narragansetts (of present-day Rhode Island) had been spared by the plague. The tribes around Plymouth Bay quickly realized it was in their best interests to ally with the English settlers.

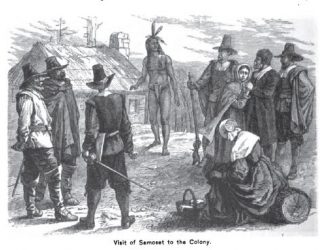

Samoset, an Abenaki chieftan from Maine who had become acquainted with European fishermen, calmly walked into Plymouth on March 16, 1621 and bid ‘Welcome’ – in English – to the baffled settlers. He asked for beer, but they had none, so they gave him ‘strong water … bisket, and butter, and cheese, & pudding, and a peece of mallard, all of which he liked well.’ The Pilgrims also dressed Samoset in a long horseman’s coat, probably for their comfort more than his, for Samoset wore nothing more than a fringed leather string around his waist.

The Abenaki chief informed the Pilgrims that Patuxet was the name of their home, but since the occupants had died four years before, the Pilgrims were welcome to stay. The next day, Samoset returned, bringing five braves with him who ‘did eate liberally’ and danced ‘after their manner, like Anticks.’ Samoset returned tools which had been stolen during the winter, introduced the Pilgrims to Squanto, a more skilled interpreter, and arranged a meeting with the Wampanoags’ chief sachem, Massasoit.

After an exchange of gifts, Massasoit made a pact with the Pilgrims: neither English or Indian would harm the other. Offenders would be punished and stolen items would be redeemed. Most importantly, if any other party made unjust war against Pilgrim or Wampanoag, the other would come to their aid. Later, when the powerful Narragansett tribe sent the Pilgrims a snakeskin wrapped around a sheaf of arrows as a warning of their might, the Pilgrims filled the snakeskin with bullets and returned it to the Narragansetts.

Massasoit sent Squanto, or Tisquantum back to Plymouth with the Pilgrims as an interpreter. In 1614 Squanto and several other Patuxet Indians had been kidnapped and sold into slavery in Spain. Luck was with Squanto, who found his way to London in the service of a rich merchant. He was placed on a ship sent to explore New England, and six months before Mayflower dropped anchor at Cape Cod, Squanto learned that his entire tribe had been slain by the plague. Squanto’s kidnapping had probably saved his life.

Without the English-speaking Squanto, the Pilgrim colony would have joined the Patuxets in death. They were running out of food, it would take months to grow crops, and there would be no rescue until ships sent by Mayflower’s captain arrived in the fall. Squanto proved to be the greatest gift the Pilgrims could have asked for.

Another valuable commodity arrived that spring – the herring run. Not only was food swarming up Plymouth’s streams, Squanto advised the Pilgrims to plant the fish in Plymouth’s sandy ground to fertilize corn seeds pilfered from Indian caches. In the fall, the Pilgrims’ peas, wheat and barley crops had failed, but they reaped twenty acres of corn (and repaid the Indians for the corn they had stolen).

With the harvest in, Governor Bradford decreed that it was time for the sort of harvest festival common in Europe. They differed from days of thanksgiving, held to note special occasions, when people met for a worship service to praise God. Days of fasting and humiliation were held during crises as the congregation prayed and searched their souls for the cause of God’s dissatisfaction.

It must be noted that the Pilgrims’ celebration was not a religious thanksgiving, for no mention was made of a special worship service by Bradford, Winslow, or the other Pilgrim fathers. Instead, they held a week of feasting and games. Edward Winslow described the preparations for ‘a more special manner [of rejoicing] together.’

The Pilgrims had become skilled fishermen over the summer, and learned to hunt turkeys and deer. In October, to their delight, vast flocks of ducks and geese came swarming to Cape Cod Bay, another cause for celebration. Winslow noted that four men went fowling, and ‘in one day killed as much fowl as, with a little help beside, served the Company almost a week. At which time, amongst other recreations, we exercised our arms [guns], many of the Indians coming amongst us, and amongst the rest their greatest king, Massasoit with some 90 men, whom for three days we entertained and feasted. And they went out and killed five deer which they brought to the plantation and bestowed on our Governor and upon the Captain and others.’

Apart from roasted waterfowl and venison, no menu was provided by the Pilgrim chroniclers. However, oysters and clams, grouse and bobwhite quail, cranberries, cornbread, watercress and other ‘sallet herbs,’ wild plums and dried berries were all readily available. Perhaps the Pilgrims had already adopted the squash and pumpkins Indians planted among their beans and cornstalks. The feast was washed down with wine made from wild grapes, praised by the Pilgrims as ‘very sweete & strong.’

None of the Pilgrims noted exactly when this festival was held, just that the harvest was finished, probably in October. More festivals would follow, along with more days of thanksgiving. We have to fast-forward to 1863 for the first national Thanksgiving Day, proclaimed by President Lincoln, to be held every year on the last Thursday in November.

Our present-day Thanksgiving follows no set pattern, varying according to the celebrants’ taste. Some Americans combine sacred elements of the Thanksgiving Day worship the Pilgrims’ held on other occasions, and their secular harvest festival. We don’t tend to feast for several days or hold shooting matches, and not all of us gather at church. However, we gather, eat, and share camaraderie, and that’s what matters. Happy Thanksgiving, everyone!

By Jo Ann Butler

**********

Fast and Thanksgiving Days of New England W. DeLoss Love 1895

William Bradford’s Journal

Saints and Strangers George F. Willison 1945

Leave a Reply