Regency society organized itself around marriage and family. Adults were identified by their place, or lack thereof, in a married, family unit. Married women were ranked higher and more respected than the unmarried. Married men were perceived as having come into their own and given the esteem and authority that went with such an accomplishment.

The plight of the regency spinster is fairly well understood. The local tax or judicial records says it all. Women were typically identified in tax or judicial records by their marital status (spinsters, wives and widows) whereas men were always identified by their occupation or social status. (Shoemaker, 1998) A woman’s identity (and legal existence) was determined by her marital status.

Spinsterhood was considered ‘unnatural’ for a woman, even though nearly one in four upper class girls remained unmarried (Day, 2006). They were called ‘ape-leaders’ (for that was what they would be doing in hell as punishment for the unnatural lifestyle. Enough said on that point….) and ridiculed for their failure in the most basic requirements of femininity.

However, if a single woman possessed independent means—a fortune of her own sufficient for her to live on, it was possible she could maintain her own household and carry on an independent life. Female investors were not unknown and their capital supported the joint stock companies behind municipal utilities and railways. Wise investments could provide a steady income without administrative worries. (Davidoff & Hall, 2002)

Not all women were so fortunate as to have independent means, and even if they were, male relatives might make it difficult or impossible for her to access her own fortune. (Naturally the men in her life knew better how to manage her affairs than she.) In those cases, a spinster would have two choices, find a job to support herself or live in the house of a relative.

Upper class ladies had limited job prospects, given their desire to remain respectable—and their more or less complete lack of marketable skills. Genteel options were limited to being a lady’s companion or a governess.

Being a governess required and education that not all ladies had and was not necessarily an enviable position. Within the households they served, the existed in a nether realm, not equal to the family but above the servants. Often, a governess would associate with neither, virtually shut away from all society. She would also be vulnerable, as all female servants were, to (unwanted) advances from the males of the household.

Unmarried women unable to become governesses were expected to make themselves useful to which ever relative might take them in. They might keep house for bachelor (or widowed) brothers or uncles, tend children, cover for married sisters while they were indisposed or during lying-in, nurse the sick, cook, clean and mend. Ironically, despite these functions, they were still often considered spungers and a burden to the household.

Today, most believe that bachelors of the era enjoyed the same social position as married men, free from the prejudice spinsters experienced. However, they too were touched by the societal bias toward the married.

This is not to say, though, that they were in any way as put upon as spinsters. The scarcity value of men in the era gave eligible bachelors the power to act as connoisseurs, holding off until the ‘right’ situation came along. (Jones, 2009) For younger sons of gentlemen, whom primogeniture denied substantial inheritance, marriage was likely to make him significantly less well off, unless of course he could find himself an heiress or woman with an excellent dowry. So, these men typically waited for marriage, often until their early thirties. But this time, they would have worked long enough to have established themselves in their profession and have the means to support a family (or attract a woman with money, which would always be an attractive alternative.)

Nonetheless, like upper-class women, one out of four younger sons remained lifelong bachelors. (Jones, 2009) While bachelorhood was seen as a natural (and possibly necessary for wealth-gathering) phase of life, the lifelong bachelor was a different creature altogether. Though not subject to the vicious ridicule heaped on spinsters, bachelors were subject to degradation as well.

In marriage, a young man took up the burdens (and the dividends—don’t forget those) of patriarchy, and became a fully realized man. In a very real sense, a man achieved political adulthood when he could support his dependents and represent their interests in the public forum. Failure to marry was often seen as being unrealized in masculinity, at the mercy of impulses and negligent in the duties to society.

“Perpetual bachelors were the ‘vermin of the state’ pronounced The Women’s Advocate … ‘They enjoy the benefits of Society, but Contribute not to its Charge and spunge upon the publick, without making the least return.’” (Vickery, 2009) The strength of this sentiment led to punitive taxes being placed upon bachelor households.

In 1785, employers of one or two male servants paid an annual £1, 5 shillings for each of them. All bachelors over 21 (the ae of majority) had to pay an extra £1, 5 shillings for every male servant they employed. Female servants were taxed at a lower rate, but bachelors had to pay double the amount. (Horn, 2004) And of course, as taxes go, the rates only increased as time went on.

Unless they were able to set up housekeeping with an unmarried female relation, sister, niece, aunt, etc. (Not a cousin mind you as they were considered marriageable and living with them unmarried would have been unacceptable.) a bachelor would have also had to pay for services usually rendered by female labor. The top four occupations for women in London 1200-1850 were washing, charring (cleaning) nursing and the making/mending of clothes, reflecting the needs of bachelors. Few women noted prostitution as their occupation, but that was a thriving trade as well. So, not did bachelors pay for their choice not to settle down and make legitimate babies in loss of social status, and taxes, but basic domestic comforts cost them dearly as well.

So, unmarried men may not have been leading apes in hell, according to regency standards, but being considered selfish social vermin was hardly desirable either. The attitude was hardly surprising though when the fundamental unit of society was the male-headed, conjugal household.

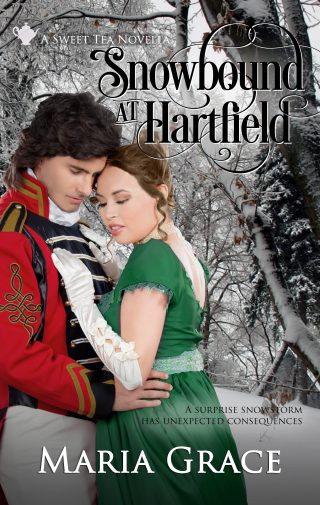

So what might happen when a dissatisfied bachelor is stranded with an equally dissatisfied spinster by a freak blizzard? This house party could turn decidedly interesting.

Excerpt: Snowbound Ch 2

After the ladies withdrew, Knightley produced an excellent bottle of port, but no cigars. Mr. Woodhouse declared them vile things indeed.

Sir Walter snorted some kind of complaint under his breath. Fitzwilliam forced himself not to laugh. He happened to share Woodhouse’s opinion.

“So you are very fond of Bath?” Bennet took a heathy draw off his glass. “My wife has on several occasions remarked upon her desire to go there herself. She has been told the waters there would do wonders for her nerves.”

“She suffers with her nerves, does she?” Woodhouse tapped the table. “My apothecary, Mr. Perry, has an excellent preparation for such things. You might acquire relief from him without the trials of traveling to Bath.”

“Do you take the waters at Bath, or perhaps partake of the hot baths?” Bennet asked.

The corner of Sir Walter’s lips curled back. “The baths are something of a mixed bag I would say. I believe they are healthful and excellent for one’s complexion. Yet, always full of skeletal frights, ridden with some sort of disease. I would be inclined to indulge more often were I not forced to look upon those poor wretches.”

Mr. Bennet’s brows flashed over his wry smile. “Fascinating observations, sir.”

“It might be wise to consider that a great number of those deformed wretches came by their injuries serving on the continent, combatting Napoleon in the service of the King.” Fitzwilliam gritted his teeth and clutched the edge of the table.

“Their service is noble to be sure, but what good is their inflicting their disfigurements upon the rest of us?”

Fitzwilliam dug his heels into the thin carpet. His scarred shoulder and thigh throbbed in time with his tense heartbeat. “I am quite certain what should not be inflicted upon us are the new whims of fashion—dandies in breeches so tight that they cannot pick up a dropped handkerchief. Those are the true bane of decent folk.”

Of course that was not a comment on the fit of Sir Walter’s breeches. Not at all.

Sir Walter sniffed. “So you consider yourself an expert on fashion, sir? I am surprised—”

Fitzwilliam rose before he realized he was moving. “Pray excuse me, Mr. Knightley. I find myself quite fatigued from the day. I believe I shall retire.” He bowed.

Darcy looked at him with that overprotective, overbearing Darcy look. At least he understood and would not try to stop him.

He might even take the baronet to task later for his attitude. Under other circumstances, Fitzwilliam might try to discourage Darcy from it. But today, it would be welcome.

“Do you require anything for your comfort?” Knightley rose, his expression mirroring Darcy’s.

“Not at all, thank you.” Unless he could provide a head full of good sense to the stupid baronet, and considering the look on his face, he probably would have tried. “Good night.”

Though Knightly might consider him rude, the risk of giving offense was worthwhile. Another minute in that fool’s presence and he would surely say something most untoward.

Mrs. Knightley had shown them a gallery not far from his chambers when she toured the house with them. Though it would not likely be lit now, it was long enough for pacing. That was what he needed. Moonlight through the windows should provide sufficient illumination for his purpose.

His boots rang against the marble, echoing like a sergeant’s voice in the narrow space.

That ninnyhammer Elliot would not survive an hour in combat. He would not even survive training. Probably would have trouble staying on his own horse.

“Oh!”

He jumped back and squinted into the shadows. Miss Elliot sat huddled in one of the hall chairs, a suspicious glisten on her cheeks.

Blast and botheration. Polite company was not what he needed now.

“Pray forgive me for startling you, Miss Elliot. Are you well? Is there something I might do for you?”

She sniffled and dabbed her face with a handkerchief wadded in her hand. “Thank you sir, but there … there is nothing I require.”

“You found the ladies’ company trying?”

“Mrs. Darcy is all that is gracious, but I often find company trying.”

“The company of married woman particularly so?” That was what Rosalind said, at least until her recent marriage.

She gasped and glared at him with eyes that blazed like rifle fire.

“Pray forgive me, I did not mean to offend.”

She jumped to her feet and stalked off.

He followed, cutting her off near the window. “Madam, I insist. Truly, I meant no offense.”

“What does it matter? I should become accustomed to it.” She turned her shoulder to him.

“You sound grievously distressed.”

“Indeed I am. But what would you care of it? It is not a matter that a man of your standing would trouble himself with.”

“My sisters often found it necessary to confide their troubles to me.”

“Indeed, what a singular notion.” Her eyes narrowed and tone sharpened to a fine edge.

That kind of a challenge was not the way to dissuade him.

He gestured toward the hall chairs near the wall. “We must have some conversation. And a substantive one is as good as any.”

“My father hardly finds it necessary.”

“Indeed.” He grunted, a sound mother warned him against in polite company.

“So he offended you—that is why you are here? Pray, do not take your offense out upon me. I am not responsible for him or his ideas any more than Mrs. Darcy and Mrs. Knightley are responsible for their fathers’ opinions.”

“Worry not. I have a father of my own whose sentiments I often find myself at loggerheads with.”

“I am pleased you understand.” She rewarded him with a brief glance.

“So, you see I am not some ogre.”

“I concede your point.”

He held out one of the chairs for her and she sat. He pulled another chair to sit in front of her. Probably a night too close, but he had to be able to see her face through the darkness, did he not?

“Are you not looking forward to visiting your Dalrymple cousins?”

She sucked in a deep breath and pressed her fist to her mouth. Her head twitched back and forth. “What do you know of my family, sir?”

Probably best to soften the truth.

“Like many titled gentlemen, debt is an issue. Sir Walter has removed his household to Bath to retrench and restore his affairs to rights. The heir presumptive, a William Elliot, keeps the daughter of the family solicitor under his protection and is not on good terms with the head of his family.”

She turned her face away, revealing a striking profile. “A most politic rendition of the tale to be sure. I had considered Mrs. Clay a friend.”

By all rights, Elliot would have done well to have married one of the Miss Elliots. No doubt she felt his defection to her friend bitterly.

“My father is deeply offended by Mr. Elliot’s actions, so much so he has been moved to drastic action.”

Drastic action often meant a duel, but the baronet did not seem the type. “How so?”

“He means to get himself a son and heir.”

“I suppose that would indeed be effective revenge against an heir presumptive.” It was a wonder he had not attempted to do so sooner.

“He means to make the dowager Lady Dalrymple’s daughter, Miss Carteret, an offer of marriage.”

Marrying a cousin was always a convenient solution. Father had once suggested he marry Georgiana.

“You believe his offer will be accepted?’

“I think it quite likely. She has youth and a handsome fortune, and he a title—not as grand as her father’s of course, but no other titled man has made an offer. They are each in want of what the other possesses.”

If would not be the first or the last such match to be made. The gossip pages would hardly notice. “You do not relish the thought?”

She snorted. “Miss Carteret is younger than I! My sister Anne’s age if not even younger. Have you any idea of how humiliating it will be to have my place as mistress of my father’s house usurped by so young a woman?”

“I have some very good idea of it.”

“A bachelor is respectable in all company, but a spinster is a blight on society.” She rose and paced along a strip of moonlight.

In the silvery light, her mask of hauteur fell, revealing a handsome woman with elegant bearing and refined features. Her figure was no longer a girl’s, but a woman’s, one refined under society’s fires.

“Forgive me, but your father’s attitudes seem a far greater blight to society.”

“Then I am doubly cursed.”

“That is not what I meant at all to say.”

She spun to face him, looking him full in the eye.

Her eyes were deep grey and quite fine.

“Then what did you mean to say?” she whispered.

“I am far more offended by your father’s diatribes on the offensiveness of ugliness than a woman …”

“You can say it, on the shelf.”

He dragged his hand down his face. “Why do you assume I mean to insult you?’

“Why should I expect anything else? My father, my sisters, even our friend Lady Russell do not hesitate to point out my flaws, however gently they try to accomplish it. I have lost my bloom. I am arrogant. I have expectations set too high—forgive me I should not speak so.” She turned her back, arms wrapped around her waist.

“What do you expect?”

“Not as much as my father used to insist I expect. A companionable man. One with enough rank in society to understand where I have come from. One with enough that he can be patient in the payment of my dowry, but not so much he would look down upon me for my father’s situation.”

“And what have you to offer such a man? You must agree a dowry which may never be paid is a strong disincentive.”

“I am well aware of that. But I fancy I can be some asset to a husband beyond a fortune. I am an accomplished woman by society’s standards. Since I have taken over the management of my father’s household, I can attest to being able to run quite a fashionable household with unexpected economy.”

He strode to look her face to face. “That is indeed a useful accomplishment.”

“I am pleased to have your approval.”

“You think a bachelor’s life far more comfortable? I assure you, if spinsters are leading apes into hell, they will find the bachelors already have a place carved out for them there.”

“That is a unique philosophy.”

“We single men do not proclaim it loudly, but it is entirely true that a woman’s hand is what makes a house a home. That is why I dread taking this estate, despite the fact I should be overjoyed now that I have true means of my own.”

“You have no sister, no aunt, no cousin to run your home for you?”

“None. My last remaining sister recently married and the only spinster aunts I have are not in health enough to keep house. I loathe the notion of being there alone and subject to the match-making machinations of the village matrons and the vicar’s wife.”

“But did you not say—”

“I do not wish to be some project, some plaything for someone to crow over. I had enough of that in the army. I do not wish to be a pawn in anyone’s games anymore.”

“It seems we share a common dilemma, sir.” She lifted her chin as if daring rebuke.

“I had come to the same conclusion. I am not one to turn away from what well may be the hand of Providence.”

“The hand of Providence?” Her eyebrow rose.

“Perhaps. Since the weather looks like we will be here several more days at least, it seems wise to see if we have the basis for the sort of friendship a married couple should possess.”

“You are quite the romantic, are you not?

“Not anymore and perhaps not ever. If that is something you expect or require, then that is the answer enough to ensure we should never begin.”

She sighed. “At one time, I may have felt that way, but I have no taste for the fancies of romance. I want a home of my own with someone whom I can like and respect.”

“So then have we a plan?”

“I suppose so, but…”

He took her hand and raised it to his lips. “Yes, we have violated every ground of propriety in being here and having this conversation at all. So then, why stop? Tell me of your last season in Bath, the entertainments you sought, the society you kept.” He led her back to the pair of hall chairs. “We have little enough time to become acquainted with one another. Let us not waste it.”

The conversation was awkward at first, but soon she revealed many pleasing opinions and a wicked sense of humor. To be sure, traces of the much-gossiped ‘Elliot Pride’ remained, but it was not far different from the ‘Fitzwilliam pride’ with which he was very familiar and even comfortable, especially from a handsome articulate woman.

References

Baird, Rosemary. Mistress of the House: Great Ladies and Grand Houses, 1670-1830. London: Phoenix, 2004.

Collins, Irene. Jane Austen, the Parson’s Daughter. London: Hambledon Press, 1998.

Davidoff, Leonore, and Catherine Hall. Family Fortunes: Men and Women of the English Middle Class, 1780-1850. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987.

Day, Malcom. Voices from the World of Jane Austen. David&Charles, 2006.

Jones, Hazel. Jane Austen and Marriage. London: Continuum, 2009.

Horn, Pamela. Flunkeys and scullions: life below stairs in Georgian England. Stroud: Sutton, 2004.

Laudermilk, Sharon H., and Teresa L. Hamlin. The Regency Companion. New York: Garland, 1989.

Martin, Joanna. Wives and Daughters: Women and Children in the Georgian Country House. London: Hambledon and London, 2004.

Shoemaker, Robert Brink. Gender in English Society, 1650-1850: The Emergence of Separate Spheres? London: Longman, 1998. Pearson Education Limited

The Woman’s advocate or The baudy batchelor out in his calculation: Being the genuine answer paragraph by paragraph, to the batchelor’s estimate plainly proving that marriage is to a man of sense and oeconomy, both a happiner and less chargeablo state, than a single life. Written for the honour of the good wives, and pretty girls of old England. London: Printed for A. Moore, near St. Paul’s, 1729.

Vickery, Amanda. Behind Closed Doors: At Home in Georgian England. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2009.

Vickery, Amanda. The Gentleman’s Daughter: Women’s Lives in Georgian England. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1998.

About the Author

Though Maria Grace has been writing fiction since she was ten years old, those early efforts happily reside in a file drawer and are unlikely to see the light of day again, for which many are grateful. After penning five file-drawer novels in high school, she took a break from writing to pursue college and earn her doctorate in Educational Psychology. After 16 years of university teaching, she returned to her first love, fiction writing.

She has one husband and one grandson, two graduate degrees and two black belts, three sons, four undergraduate majors, five nieces, is starting her sixth year blogging on Random Bits of Fascination, has built seven websites, attended eight English country dance balls, sewn nine Regency era costumes, and shared her life with ten cats.

She can be contacted at:

English Historical Fiction Authors

Leave a Reply