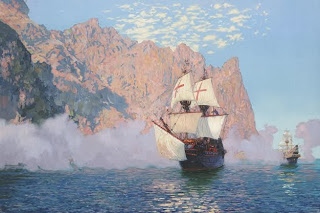

“The Golden Hinde off New Albion”

“The Golden Hinde off New Albion”

by Simon Kozhin, oil on canvas, 2007.

Little is known about the Golden Hinde even though she is one of the most famous sailing vessels in maritime history. No one can say for sure if she was built in England or if she was a prize of war. Originally christened the Pelican, she was the flagship of the small fleet in which Francis Drake and 164 men, gentlemen, and sailors embarked from Plymouth, England in 1577 on the three-year adventure that would become the second successful circumnavigation of the world—and one of the most profitable pirate voyages of all time.

Drake changed the name of the Pelican to the Golden Hinde just before the fleet entered the Straits of Magellan in late August, 1578. He did so “in remembrance of his honorable friend and favourer,” Sir Christopher Hatton, a major backer of the expedition and an intimate of the queen, since Hatton’s family crest was a “hind trippant or.”

Drake felt the need to flatter Hatton because he feared the lord—one of his employers—would be displeased with him upon learning that Drake had executed Thomas Doughty in July for reasons that are still unclear. Doughty, a co-captain of the adventure, had been Hatton’s personal secretary. Presumably Hatton had recommended Doughty for the leadership position he held until the headsman’s blade terminated his contract.

Three vessels attempted the Straits. All made it through but the Elizabeth retreated to England and the Marigold sank with every hand in the Southern Ocean. Only the Golden Hinde continued the voyage, taking the Spanish treasure ship Nuestra Señora de la Concepción, charmingly nicknamed the Cacafuego—the Shitfire—and returning home with sufficient treasure to pay off the English national debt and to make millionaires of Drake and his investors. After being gifted with £100,000 in gold, a diamond cross, and a crown studded with emeralds, three as long as a finger and two round stones valued at 20,000 crowns, Queen Elizabeth knighted Drake on the deck of the Golden Hinde.

Then the ship was retired from service and moored permanently at Deptford on the south bank of the River Thames, where she became a national tourist attraction. Pedestrian walkways were built around her for the convenience of spectators and the entire vessel was roofed over to protect her from the elements. For the next eighty years the Golden Hinde drew crowds of visitors from across the country eager to see the ship in which Drake had made his celebrated voyage. Eventually, though, time and rot and pilferage wore away at her. In 1662 the Golden Hinde was broken up. No trace of her remains today although according to rumor bits of her timber were used in the construction of certain items of household furniture. Tables in the Bodleian Library, Oxford, and in the Middle Temple Hall, London, as well as a chair in the great hall of Buckland Abbey, the estate Drake purchased with proceeds from the adventure, are all supposed to incorporate wood from the ship.

Only one authentic picture of the Golden Hinde survives. This is an engraving on a coconut shell, currently in the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, which Drake presented to the queen as a souvenir. Unfortunately, the carving lacks detail and little about the actual vessel can be learned from it.

What is certain is that the Golden Hinde was a galleon, which is unsurprising since galleons were the marine workhorses of the 16th century. Their compact design allowed them to be used equally well as merchant ships and as military vessels. Most displaced less than 500 tons and carried three masts, two square-rigged and one lanteen-rigged. From their 15th-Century predecessor, the carrack, they inherited high forecastles and bulky sterns, which provided a ship’s crew the advantage of elevation while battling another vessel at close quarters. The Golden Hinde, however, was race-built, after plans developed in France and promoted in England by Sir Richard Hawkins. This meant her fore- and aft-castles had been razored down, decreasing her windage, making her fast and agile, as well as better suited for naval warfare that relied on artillery rather than on hand-to-hand combat.

According to modern estimates, the Golden Hinde was 102 feet long, excluding her bowsprit, from which hung a rectangular sail known as the spritsail. Her beam was 20 feet. She displaced between 100 – 120 tons. She did not have a figurehead. Nor did she have a steering wheel—the rudder was controlled by a system of long rods known as a whip-staff. Her masts rose over eighty feet above the deck, exposing four thousand square feet of canvas to the wind, allowing the ship to make eight knots in a fair breeze. Between the lower and upper halves of her main masts were platforms known as fighting tops, which served as fortified roosts for archers during battle. Her sails were plain flax, except for the top fore- and main-sails, each of which was emblazoned with a red cross. This is how Nuno da Silva, the Portuguese pilot kidnapped by Drake in the Cape Verdes, described the Golden Hinde when questioned by Inquisition officials in 1579:

“The Capitana [Golden Hinde] is in a great measure stout and strong. She has two sheathings, one as perfectly finished as the other. She is fit for warfare and is a ship of the French pattern, well fitted out and finished with very good masts, tackle and double sails. She is a good sailer and the rudder governs her well. She is not new, nor is she coppered nor ballasted. She has seven armed port-holes on each side, and inside she carries eighteen pieces of artillery, thirteen being of bronze and the rest of cast iron, also an abundance of all sorts of ammunition of war… Taking it all in all, she is a ship which is in a fit condition to make a couple of voyages from Portugal to Brazil.”

Although a 100-foot ship may seem tiny today, when cruisers, cargo vessels, and tankers regularly exceed 1,000 feet in length, it is important to realize that the Golden Hinde was small even in her own era, particularly considering how heavily she was burdened and how many men she carried. In the 16th Century a merchant ship her size would have had a crew of less than twenty officers and sailors since then, just as in our own time, the cost of labor affected the profitability of any enterprise. More than sixty men, however, sailed aboard the Golden Hinde. This company included a dozen gentlemen adventurers, investors in the voyage and their relations, as well as soldiers and armorers; artisans such as smiths, coopers, carpenters, and sail makers; a troupe of musicians; a pastor; and additional sailors. All these extra men were needed not only for their professional expertise but as replacements for those expected to die during the voyage. They were also needed to man the cannon, which each required a gang of three or four men to operate efficiently.

It is estimated that the Golden Hinde carried enough supplies to allow even so large an expedition to remain independent of the land for six months to a year. A partial inventory has come down to us:

“Woode, coale, candles, wax, lantens, platters, tancardes, Jackes of Lether, dyshes, bowles, bucketes, taper caundles, scoop shovels, mattocks, hachetes, crows of iron. Compazes, Ronnynge glases, Lamps, water caske. Whoops of Iron & Woode. Cordage, canvas, pitche, tar, Rossen, flat leade, roughe leade, nails, spiekes, sownding leades. Lyenes marlyn, ratlyne twyne, nydles pulles, nessesares for fyshinge as netes, hookes & Lynes mowntes. Woollen & Lynnenge clothes, shows, Hates, caps &etc. Aprovition for the surgeons.”

The heaviest and most bulky items—spare masts and anchors, cannon shot, several disassembled pinnaces, as well as the gold and silver looted from the Cacafuego—were stored in the bottom-most deck of the ship, the hold or bilge, where they acted as ballast and helped stabilize the vessel. The next deck up, just below the waterline, was the orlop, which held the hardware mentioned above and also the fresh and dried victuals for the voyage—barrels of salted pork, beef, and cod; rice, peas, walnuts, and sugar; biscuit and meal; vinegar, mustard, and spices; kegs of water, beer, and wine; and a menagerie of livestock and poultry. The upper-most full deck was the gun deck. Most of the space here was taken up by the massive eight-foot barrels of fourteen cannon known as demi-culverins. Despite being crowded with artillery, the gun deck served as the living quarters for the ordinary crew, the sailors slinging their Brazil beds—hammocks—between the cannon or sleeping on straw on the planking. It is possible that parts of the gun deck and the orlop were sectioned off into cabins by canvas partitions, since it is known that the Golden Hinde had both an armory and a smithy.

At the front of the vessel above the waterline was the half deck known as the forecastle, which held two forward-facing cannon, bowchasers. The center of the ship, the waist, was open to the air and floored with grates instead of planks, allowing light and atmosphere down into the gun deck. At the rear of the ship was the afterdeck, which housed the grand cabin and Drake’s personal living quarters. Finally there was the poop, also known as the roundhouse, a small cabin in which Drake and his officers relaxed in comfort during the long oceanic passage to Brazil.

There is a scale replica of the Golden Hinde moored in London on the Thames, which I visited in 2009 while researching my novel about the circumnavigation, At Drake’s Command. Although liberties were taken with the design—the replica possessed both a figurehead and a wheel instead of a whip-staff—in most respects meticulous attention was paid to re-create the original vessel exactly. Her hull was painted black and detailed with alternating bars of gold and scarlet, colors known to be popular with Tudor shipbuilders. The deck beneath my feet was painted red, too, as it would have been in Drake’s time, in order to hide spilled blood. Walking the ship I had studied for so long, I began to understand the enormity of the achievement of the men who had sailed her. For three years they lived cheek to jowl in a claustrophobic wooden world surrounded by enemies, enduring storm and flat dead calm, foul water and rotting meat, the arrows of hostile Indians and Spanish lead—and yet they survived and triumphed. As I stood on the afterdeck beside the mizzen-mast, the very spot where Drake would have stood while commanding the vessel, I felt an obligation to these brave men and to this small ship to do my best to capture their story in words as truly as I was able.

Read more about David Wesley Hill and the artist Simon Kozhin

Leave a Reply