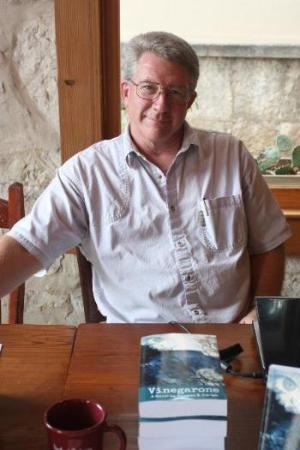

We’d like to welcome two time award winning author Douglas Carlyle to take part in our crime fiction week.

Doug, when writing crime fiction, there is usually several characters involved. What is your advice in presenting each character so they stand out?

There will be a protagonist and an antagonist in any crime fiction novel. Both must have a strong presence. The author must directly and indirectly describe the physical and intellectual attributes of the good and evil characters, but only with enough detail so as to allow the reader to embellish with his or her own pallet of colors. As the author, I find opening the window to the inside of our hero (heroine) and villain equally exciting.

However, for me, one distinguishing feature is that as for the protagonist, humor sets that character apart from the antagonist. I’m not speaking of being a deadpan jokester. Rather, he/she may have a dry wit, colorful language, peculiar quirks. Humor attracts the reader to the good side and allows them to fall in love with that character.

I think it is important for writers to give conflicting reasons for their characters to be criminals. For readers to find that connection-if you will-or to perhaps sympathize with them. How do you pull that off and what is your advice on doing so?

This is quite tricky. The author must not give away the true identity of the real criminal until the end of the novel. As such, the author must lead the reader toward one or more characters who the reader strongly feels could be the criminal, all the while disguising the villain.

To pull this off, the author must leave clues hinting a certain character could be responsible for the crime. Most readers are smart enough to know the most obvious characters the author casts as the “bad guy” are simply red herrings. Yet, the author must leave just enough doubt in the mind of the reader to keep them on the hook. In my crime series, these “almost villains” often have extreme personality traits. As an example, they may be very brash during any conversation. They avoid contact in some circumstances. They have mannerisms that display a certain degree of discomfort when in the company of the protagonist. The back story to these characters may be excessive greediness, alcoholism, substance abuse, damaged personal or familial relationships, an unhappy childhood – all traits that may appeal in some way to the reader in a very personal way.

Then, basinga! The true villain appears. The protagonist and antagonist then stitch together some sordid story that, in the mind of the criminal, justifies his/her actions. There has to be just enough ah-ha that the reader can say to himself, “Yes! That makes sense!”

Crime Fiction can be difficult to write because it contains many plot-lines. How do you keep track on who has done what and when?

I write in multiple genres. In each of my novels there are many plot-lines. This is a problem that is not unique to crime fiction.

In my first three novels, I based the central character on aspects of my own life. As such, I was embedded within my own novel. This made it easier for me to maintain continuity.

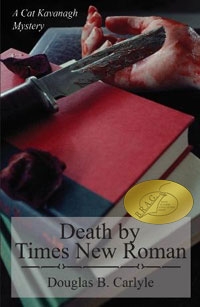

With my crime novel, I was for the first time truly looking down at all of the action. I actually make continuity more difficult for myself in that the duration of the novel—the period from start to finish of the actual story—is quite short. In Death by Times New Roman we are talking about less than a week. A lot takes place in a short time. I found myself having to manage each scene, while at the same time ensuring the sequence of events was correct. What is more difficult, however, is what’s going on backstage. The characters that are not a part of each scene are actually doing something vital to an upcoming scene or perhaps the pinnacle moment in the novel. It must make sense that those off-screen actions could have actually taken place in order to make the reader believe that it happened. Readers for the most part are quite intelligent. They can recognize a continuity mistake quite readily.

I can honestly say that I keep track of events and a calendar on a separate piece of paper. Even this is imperfect. I catch many continuity errors in my many start-to-finish reviews of the entire manuscript. I probably read each of my manuscripts three or four dozen times before I send it off to my editor. Then my editor catches other continuity errors and we must go to work.

These continuity errors are among the most difficult editorial changes an author has to make, often necessitating significant re-writing of material.

Crime fiction must be believable. Real-life for the basis of your story is important. How do you corporate this?

First of all, I choose a setting that is more real than fiction. All of my novels have take place in real locations with which I am quite familiar that I adjust a little here and there so as to not offend anyone.

While the story must be believable, I think it is important for the author to push the limits of the imagination lest the reader get bored. I named the protagonist in my crime series Cat Kavanagh. I have had reviews that say, “She isn’t quite believable.” Yet, I based her upon a real person. This person just happens to be one who is larger than life with star qualities. She is gorgeous, has the physique of a pentathlete, had a terrible childhood, managed to garner a degree in physics with a minor in chemistry, is a bit of a nymphomaniac, and is a decorated U.S. Army veteran with combat related PTSD. If that doesn’t give me room to play, I don’t know what does.

How do you prevent your story from becoming boring?

The mathematical equation by which I write is: Dialogue > Narrative. Dialogue keeps a story moving. Narrative maintains place and time. Both are vital, but dialogue controls the pace. If you cannot write good, believable dialogue, you should look for another vocation.

And while I wouldn’t even consider my novels to be close to soft-porn, all of my readers look forward to that one (okay, maybe two or three) spicy scene.

How should a writer “not” start the opening line to their crime story?

In general terms, I want to introduce the real criminal early. I want them to be a part of the entire novel. I simply don’t reveal them until then end. As such, don’t avoid bringing in the antagonist right away.

In specific terms, I like starting with dialogue. Don’t begin with some long, drawn out narrative.

What are the key components in writing crime fiction you might not have mentioned above?

There must be twists and turns in the plot, but, there can be too many. I believe in closure. Don’t leave a sub-plot unresolved. If you are unable to “tidy up” all of the loose ends and still make your novel a length that is tolerable for your readers, you need to start cutting.

What are the crime thrillers you read to inspire you?

What little I read has been devoted to Sandra Brown and a largely unknown, yet outstanding Texas author, Kit Frazier. Both use funny, lively, sexy heroines much like my Cat Kavanagh. They gave me great inspiration.

Author Website

Leave a Reply