Stephanie has asked psychological and crime fiction writer Debrah Martin (also writing as D.B. Martin) how she tackles writing a thriller. Here are some of her suggestions.

Q: When writing crime fiction, there are usually several characters involved. What is your advice in presenting each character so they stand out?

A: Crime writing is really no different to any other kind of fiction writing. The characters have to be credible and likeable – or so wholly unlikeable/intriguing that they still fire the reader up enough to want to find out what happens to them. Spend some time deciding on your individual character’s strengths and weaknesses, their challenges or their nemesis. We all have an Achilles heel. What is theirs? What is it that forces your protagonist to take up the fight – or commit the crime? And how will they ultimately redeem themselves, or ‘face the music’. I usually pick from something like this to set up the main personality traits for each of my characters:

Then I pair, group and counterpoint them between characters. Physical attributes can sometimes complement or highlight personality traits too. Then I think about where they will fit in the plot, and how they will move the plot forward. For example, Lawrence Juste in the Patchwork Man trilogy, one of the characters is all the attributes highlighted in both pink and yellow; good and bad. Ultimately, some readers say s/he is their favourite character, although it takes a while for all of the yellow to outweigh the pink. S/he is possibly my favorite too – although I’m not saying who they are! However, what causes readers to react is the dichotomy that is her/him.

Then I pair, group and counterpoint them between characters. Physical attributes can sometimes complement or highlight personality traits too. Then I think about where they will fit in the plot, and how they will move the plot forward. For example, Lawrence Juste in the Patchwork Man trilogy, one of the characters is all the attributes highlighted in both pink and yellow; good and bad. Ultimately, some readers say s/he is their favourite character, although it takes a while for all of the yellow to outweigh the pink. S/he is possibly my favorite too – although I’m not saying who they are! However, what causes readers to react is the dichotomy that is her/him.

Q: I think it is important for writers to give conflicting reasons for their characters to be criminals. For readers to find that connection-if you will-or to perhaps sympathize with them.

How do you pull that off and what is your advice on doing so?

A: We could all potentially be criminals, do you not think? What makes someone a criminal is that they simply do something outside of the law. How many times have you dropped a piece of litter when there are fines for littering? Or jumped a red light? Or speeded? Some things are minor crimes, and some are major, but even minor crimes can have a major effect. What if, in jumping that red light, you run over a pedestrian? What if you then don’t stop, and the pedestrian dies. Jumping the light is minor, killing someone is major, and yet the driver may be someone like you or me – late for an appointment, or tired and not concentrating properly, or upset, or ill – or so many reasons I could fill a page with them. They are not evil, they are simply human. Sometimes a criminal is born simply from circumstance – the random accident – and then the story is about how they deal with it. Sometimes they are born from a collision of circumstance and themselves – how their beliefs or motivations interact with the situation they are in to dictate a particular outcome. Get to know your character really well before you set them on the run. Make them human. Show what makes them tick. Then push them over the edge. How can a reader not have sympathy for character if they can imagine themselves in their shoes?

Q: Crime fiction must be believable. Real-life for the basis of your story is important. How do you incorporate this?

A: To be credible, a plot should unfold before them in such a way that it is possible for a reader to look back at the end of the book and say, ‘ah, now I see where that came in!’ Unfortunately some books with really great plots don’t do that well enough, even though they are best sellers because of the ‘twist’. You need to be able to see where the ‘twist’ was seeded for it to be a really well-planned plot. To my mind, whilst being an interesting story, ‘The Girl on the Train’ falls down here. When did the idea that Tom was anything other than a good guy get introduced in the guts of the plot? Rather, it appears Deus ex Machina right at the climax as a ‘tah-dah!’ moment, a bit like Agatha Christie loved doing when Miss Marple or Hercule Poirot suddenly revealed the identity

of the murderer. Setting is important too. Create a real world, with real people and real motivations, and you are most of the way there. Look around you. You can examine anyone you know and be intrigued by their private agenda if you employ a little objectivity. Observation is key. Observe people, observe places and observe situations. Then describe them well. That old ‘show’ not tell. Interestingly I have been considering this from a different viewpoint recently because I have been attending a screenwriting class, where it’s all about mood and presentation. What does the opening sequence of a film tell you about the film? Try watching one and you will see what I mean. It can be applied equally well to novel writing. Set a mood, set a tempo and set a type of story and your novel’s world becomes real.

of the murderer. Setting is important too. Create a real world, with real people and real motivations, and you are most of the way there. Look around you. You can examine anyone you know and be intrigued by their private agenda if you employ a little objectivity. Observation is key. Observe people, observe places and observe situations. Then describe them well. That old ‘show’ not tell. Interestingly I have been considering this from a different viewpoint recently because I have been attending a screenwriting class, where it’s all about mood and presentation. What does the opening sequence of a film tell you about the film? Try watching one and you will see what I mean. It can be applied equally well to novel writing. Set a mood, set a tempo and set a type of story and your novel’s world becomes real.

Q: Crime Fiction can be difficult to write because it contains many plot-lines. How do you keep track on who has done what and when?

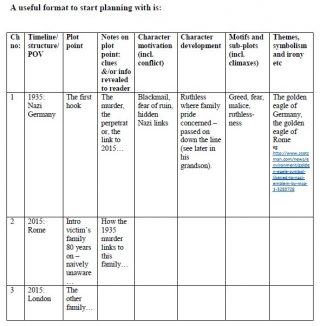

A: A spreadsheet! I also keep a summary of each chapter so it is relatively easy to go back to who/what/where when I need to. A summary of important facts, names, dates, places is important too. Sometimes I spend ages working out who would be how old and when just to get the facts right. I’m doing that now with the book I’m currently working on. It is important to make sure you don’t make things too complicated though as whilst you, the writer, are au fait with the whole thing, of course your reader isn’t. Layering is the best way to achieve this. Don’t have just one plot, have several – all impacting on each other.

A: A spreadsheet! I also keep a summary of each chapter so it is relatively easy to go back to who/what/where when I need to. A summary of important facts, names, dates, places is important too. Sometimes I spend ages working out who would be how old and when just to get the facts right. I’m doing that now with the book I’m currently working on. It is important to make sure you don’t make things too complicated though as whilst you, the writer, are au fait with the whole thing, of course your reader isn’t. Layering is the best way to achieve this. Don’t have just one plot, have several – all impacting on each other.

Q: How do you prevent your story from becoming boring?

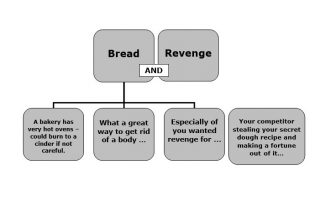

A: Pace, hooks, climaxes and anti-climaxes. And interweaving people, motivations, challenges, situations – and as mentioned above; many plot lines. Think about real life again. We may have many different motivations for wanting a specific thing to happen, or not happen. So will the characters in a book.

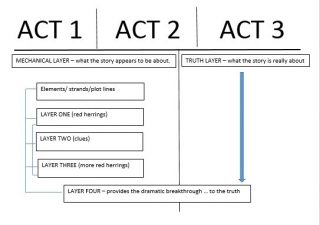

There may be many different strands to what actually happens in relation to any one event, depending on which character’s life story we are following at the time. Their story line may be tangential, but still having some bearing on the main plot. It may cross the main plot. It may deflect the main plot and send it spinning in another direction. It may simply inject an element of human interest. It is the complexity and depth provided by multiple plotlines that keep a story from being simply beginning, middle and end.

There is also something called the Three Act Structure, which gives a plot line sufficient substance to hang together. I write a lot more about this in Write, Publish, Promote, and how to use it effectively in your writing.

Q: How should a writer “not” start the opening line to their crime story?

A: I don’t think there is an answer to that, other than ‘with the obvious’ – and even that doesn’t hold true in all cases. Sometimes the obvious – the crime itself is actually the most effective. I would rather comment on how a writer should start their crime story; with the intriguing, the unique, the flavor of their characters and the world they inhabit, with the quirky, even the downright odd. Everyone knows the iconic first line of ‘1984’. There you are: emulate that!

Q: And the ending?

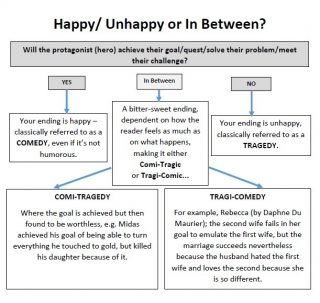

A: Make it satisfying, make it real and make it linger on in your reader’s mind. Not all endings are happy. I watched the film ‘Manchester by the Sea’ recently and the ending was perfect – but not happy. My Chained Melodies – not a crime fiction per se, but it does have a crime in it – is not the perfect happy ending. But life is like that – not perfect. What a writer should do is craft an ending that is perfect for the story itself. What would I have done, if that had been me? What will they do now? What might happen next?

Q: What are the key components in writing crime fiction you might not have mentioned above?

A: Factual accuracy. If you have procedural elements, research them thoroughly. If you are building your plot around dates or timings, test them out (although, obviously, don’t go out and murder someone to do so). If you need medical or forensic information seek it out. I once found an amazing website where the site owner (a forensic scientist) would kindly answer writer’s ‘what if’ questions about so google your question and see who can answer it for you. Writing is about suspension of belief – but only if that suspension of belief is credible. You don’t have to be 100% informative. You can leave some lines of enquiry oblique, but do make sure it could be possible.

Q: What are the crime thrillers you read to inspire you?

A: John Fowles – ‘The Collector’; truly creepy for psychological thriller writing. PD James, Barbara Vine etc for brilliant police procedurals. Jo Nesbo for thrillers with a horrific twist – very noir! There are many thriller writers out there and it is too easy to fall into the abyss that is crime and be lost. Be unique.

You can find a lot more writing tips, as well as information about self-publishing and book promotion in Debrah’s Write, Publish, Promote, from which some of the diagrams and illustrations in this blog post have been drawn. And you can simply follow Debrah or get in touch with her through any of the links below:

You can find a lot more writing tips, as well as information about self-publishing and book promotion in Debrah’s Write, Publish, Promote, from which some of the diagrams and illustrations in this blog post have been drawn. And you can simply follow Debrah or get in touch with her through any of the links below:

Her website (and where you can see the type of books she writes) is:

A free copy of Patchwork Man (digital) can be downloaded via this sign up link

Find her on Facebook here: https://www.facebook.com/DeborahMartin.Author/

And on Twitter here: https://twitter.com/StorytellerDeb

Her UK based writing and self-publishing courses can be found here: Courses and Resources

Or just say hello here: info@debrahmartin.co.uk

Debrah’s books

Link for Patchwork Man

Link for Chained Melodies

‘Images are drawn from Write, Publish, Promote and reproduced with kind permission of Debrah Martin. Please note they are protected by copyright and should not be copied or reproduced elsewhere.’

Leave a Reply