Martha Kennedy

Author of indieBRAG Medallion Honorees, Martin of Gfenn and Savior

It’s estimated that as many as 20,000 Swiss emigrated to America before 1820, bringing not only their hard-working, flesh-and blood-selves, but religious and political philosophies that influenced what this nation became. I knew nothing about any of this until, at the suggestion of a Swiss reader of Martin of Gfenn, I began researching my own family tree. There I met the Schneebelis.

At the time, I was in the midst of writing Savior, the story of a 13th century Swiss family, very minor nobility, living in a castle-fort near Affoltern am Albis in the Canton of Zürich. I based the setting of my story on a hillside and castle ruin I’d seen on a hike with a friend. I was dumbfounded when, in the midst of “finding my roots,” I found that my own ancestors had lived on that very hillside and in that very castle-fort. Even more creepy, the people in my family had the same names I’d given the characters in my story. OK, it’s true that there were not many names used in those places in the 13th century (boys were usually Rudolf, Hugo, Conrad, Hans or Heinrich; girls were commonly Margaret (Gretchen), Anna, Elisabeth or Verena), but it was still weird enough to keep me awake for a couple of nights.

The discovery also gave me the ending for Savior, one far different — and better — than I had first envisioned.

When I had finished Savior, I climbed up my family tree to the years of the Zürich Reformation. Three hundred years after the (99.9% fictional) events depicted Savior, the family still lived in Affoltern am Albis. The family had six living sons; Heinrich, Hannes, Peter, Conrad, Thomann, and Andreas. My personal ancestor was the oldest, Heinrich. This discovery evolved into my third novel, The Brothers Path, a loose sequel to Savior. The story takes place between1524 and 1531, the seven most turbulent years of the Protestant Reformation in Zürich.

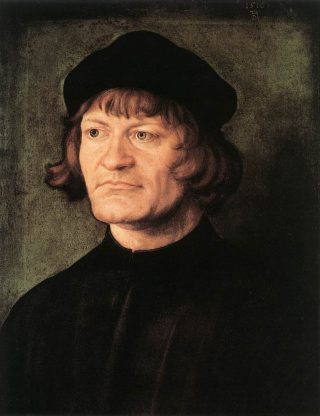

Having visited Zürich a few times, I knew a little about the Zürich reformation. I knew Huldrych Zwingli, the leader, was regarded as a hero of religious freedom. The modern doors of the Grossmünster depict scenes from Zürich’s religious history, focusing on Zwingli and his great deeds.

Huldrych Zwingli and Martin Luther were contemporaries. They had numerous formal debates over doctrine and ultimately were unable to reconcile over the question of transubstantiation. Luther said, “Yes,” and Zwingli said, “No.” Looking back through five hundred years of “how things turned out,” the big difference is that Martin Luther lived to see his reforms expand into a major religion, and Huldrych Zwingli was killed early on in a war with the neighboring Catholic Swiss cantons.

In my research, I always try first to look at primary sources, the direct and authentic expression of people living in the past. In them I have some chance of finding the beliefs and biases of the world in which my characters lived. I read sermons, treatises, edicts, letters and laws, but rather than being excited and exhilarated by what I was learning, I was often disgusted. The more I read of and about Zwingli, the more I saw a demagogue who had emerged at exactly the right moment in Zürich politics to liberate Zürich’s coffers from the Roman church. Zwingli also became the first Protestant leader to execute another Protestant, condemning his former friend, Felix Manz, to death by drowning over the question of infant baptism. The torture, imprisonment and execution of Anabaptists (rebaptizers) in Zürich would continue for two-hundred years.

I also discovered I had strong feelings about all of this that I would have to overcome if I were going to be fair to the people who had lived so long ago in a world that did not belong to me.

I tried to imagine how all this might have been for the characters in my story who were living in the midst of a revolution. How did they contend with these changes, not knowing how things would turn out, not knowing, even, the long-term significance of everything happening around them?

I found a few facts about the family. Their father, Johann, had married a girl, Verena, whose father owned a mill in the nearby village of Thalwil. Johann would come to own that mill and another in Affoltern am Albis, their original home village. History also shows that the Schneebelis were not doing so well in the 15th and 16th centuries, but that Johann recovered the family fortune. He also served on the Zürich council.

The record also says that Hannes and Peter were priests. In Peter’s case, I had to imagine the life trajectory of a man who went from being a military leader at the Battle of Marignano, one of the bloodiest of the Papal Wars, to being a Dominican friar (although married), and finally becoming a Reformed pastor in the Canton of Glarus. The facts exist, but the bridges between them were up to my imagination.

Less is known about Hannes, but, as a second son, he could have been “given” to an abbey to be raised as a priest. Hannes’ abbey (as part of Canton Zürich) would have been “reformed” before 1531. Because I had already written of an abbey and its chapel in Savior, I used it to tie the stories together.

Hannes needed a motive to leave the Catholic church after which he would then, naturally, attend the school begun in Zürich by the reformers to train pastors in the new religion. I was very happy to find the texts of the lessons given at this school, and it was natural to include some in my novel as Hannes would have heard them.

I took the reformation of Hannes’ abbey as an opportunity to make the point that not everyone hated The Church, but that for hundreds of years it had held an important and beloved place in many peoples’ lives. I wanted to show this, and I could through the character of the abbey’s prior and a small, wooden Madonna that had been important to Rudolf, the protagonist of Savior and ancestor to the characters in The Brothers Path.

Anabaptism was well entrenched in Affoltern am Albis by the 17th century. A member of the family, Heinrich Schneebeli, was imprisoned in Zürich for Anabaptism in 1640, so it seemed likely to me that, when Anabaptism emerged, at least one of the six Schneebeli brothers would have followed the teachings of the so-called “Radical Reformation.” In The Brothers Path, Andreas, Thomann and Heinrich’s son, Heinj, are Anabaptists.

Historical fact and primary sources gave me an armature on which to build a story about six brothers trying very hard to discover — and do — the right thing in a world where every understanding of right and wrong had been turned upside down.

Another great post by Martha Kennedy: Inspiration’s Mysterious Power

My passion for history grew directly out of reading authors like you, though probably not as accurate as you. Still, historical fiction was the backbone of my independent, out-of-school education. I can’t even imagine who I’d be without all of those historical stories. They got me searching the dusty backrooms of libraries to find the real characters … and I’m still searching more than 50 years later.

I think mine love for history had a similar source. As a young person I read whatever was on our shelves. My mom was an avid reader of historical fiction — her favorite writer was Irving Stone but she also loved Michener’s work.